I finally dove into the towering theologian Karl Barth’s (1886 - 1968) writings and was surprised at the amount of geometry that factors into his theology. Here’s a look at one of his more extended math metaphors.

Intersecting planes

In his commentary The Epistle to the Romans1 on the letter of the same name, Barth engages in an extended visualization of how an infinite and transcendent God interacts with the finite world via the Son, the second person of the Trinity, the incarnate Word of God2. He paints a geometrical picture (spacing and emphasis mine throughout this post):

In this name [of Jesus Christ our Lord] two worlds meet and go apart, two planes intersect, the one known and the other unknown. The known plane is God’s creation, fallen out of its union with Him, and therefore the world of the ‘flesh’ needing redemption, the world of men, and of time, and of things – our world. This known plane is intersected by another plane that is unknown – the world of the Father, of the Primal Creation, and of the final Redemption. The relation between us and God, between this world and His world, presses for recognition, but the line of intersection is not self-evident.

So we have two planes – but this is not the clichéd “two planes of existence” idea that permeates lots of dualist pop culture, where the physical and the spiritual operate mainly in parallel until some supernatural plot device brings them into relation.

These planes are not the typical material vs. immaterial worlds, but the planes of fallen time and space vs. the redeemed Kingdom of God. We can speculate in this image that the entry of sin into the world knocked this first, known plane off its axis, setting it at a skew to the second, unknown plane, so that they continue to intersect at a single line.

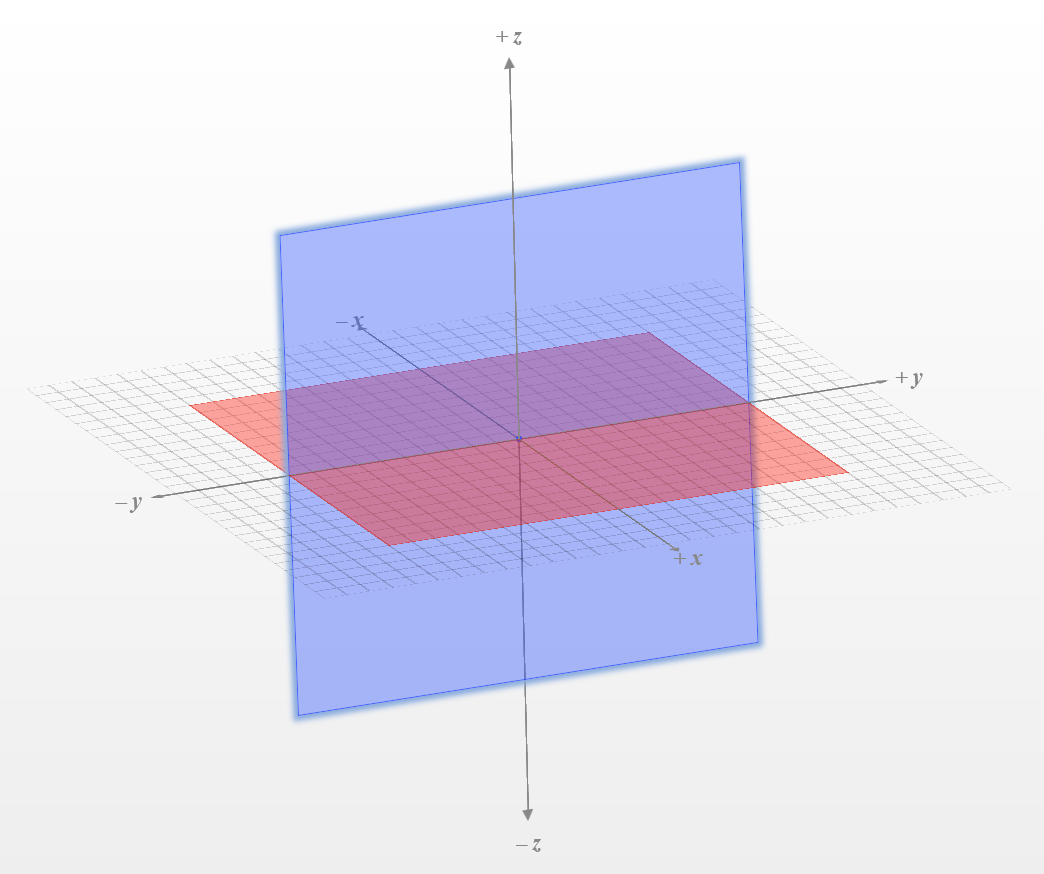

Let’s take some 3D planes as an example for visualization.

Here we can take the red, horizontal plane to be Barth’s known plane and the blue, vertical one to be his unknown one. Set at a 90-degree angle from each other, the planes intersect at a single line, here the y-axis.

How can anything on the known plane apprehend the existence of the unknown one, when their line of intersection is not clearly visible? Barth says that one particular point along this line was visible:

The point on the line of intersection at which the relation becomes observable and observed is Jesus, Jesus of Nazareth, the historical Jesus – born of the seed of David according to the flesh. The name Jesus defines an historical occurrence and marks the point where the unknown world cuts the known world.

Here Barth sets himself in contrast with his liberal theologian peers: Jesus was a real man in history who did not just symbolically suggest the philosophical union of God and man but actually embodied it, as the sole visible point along the line of intersection between fallen and unfallen planes.

Intersecting time and eternity

Even more than that, Barth suggests that as this visible point, Jesus embodied the finite and the infinite on the line of intersection between creation in time and God outside of it:

This does not mean that, at this point, time and things and men are in themselves exalted above other times and other things and other men, but that they are exalted inasmuch as they serve to define the neighbourhood of the point at which the hidden line, intersecting time and eternity, concrete occurrence and primal origin, men and God, becomes visible. …

Characterizing the planes this way is not a matter of saying the known one has time and the unknown one does not have time. We should instead think of “eternity” as above time, where we, being temporal, can only see cross-sections of an such an object at a time. To consider this, we can perform the famous thought experiment provoked by Abbott’s Flatland, a novella where two-dimensional creatures are visited by creatures from a third dimension.

A Victorian drawing from Edwin Abbott Abbott's novella, Flatland. Yes, that's really his name -- his parents were cousins.

Abbott’s classic illustration above shows what would happen when a 3D object, comprising a dimension above a 2D object, passes through a 2D plane. If we were 2D creatures living in Flatland and such a 3D sphere descended to us, we would have no way to visualize its 3D nature – instead, we would see its appearing as sequential circular cross-sections that grow bigger when the sphere intersects our 2D plane at its middle and smaller as it recedes from it.

We can extrapolate the analogy by one when considering time, a “fourth dimension”. Being temporal 3D creatures, we can only apprehend cross-sections of objects that comprise that fourth dimension. Returning to Barth’s planes, we might suggest that while the known plane is indeed “all there is to it” – it comprises the true nature of fallen creation – the unknown one may merely be a cross-section of a transcendent sort of “object”, a higher-dimensional space comprising the Kingdom of God, that is intersecting with us.

The impact of a point

Barth holds tightly to the mathematical notion that a point is infinitesimally small. Jesus Christ, the sole visible point on the line of intersection, brings the Kingdom of God to touch our own world, but how can an infinitesimally small thing ever touch another thing?

He asserts that all of the hubbub caused by Jesus the historical person’s life, death, and resurrection is not that other world – the planes remain intersecting planes:

The point on the line of intersection is no more extended onto the known plane than is the unknown plane of which it proclaims the existence. The effulgence, or, rather, the crater made at the percussion point of an exploding shell, the void by which the point on the line of intersection makes itself known in the concrete world of history, is not – even though it be named the Life of Jesus – that other world which touches our world in Him. In so far as our world is touched in Jesus by the other world, it ceases to be capable of direct observation as history, time, or thing.

But Barth follows Paul’s line in the Epistle that is the subject of this work. Paul proclaims that the event of Jesus’ actual, historical resurrection (again a contrast to Barth’s liberal contemporaries who suggested a purely symbolic reading) underlies another transcendent event, namely, the metaphysical declaration of His status as the Son of God.

Jesus has been [“]declared to be the Son of God with power, according to the Holy Spirit, through his resurrection from the dead[”]3. In this declaration and appointment – which are beyond historical definition – lies the true significance of Jesus.

Then Barth brings it all together. What is the unknown plane, really?

As Christ, Jesus is the plane which lies beyond our comprehension. The plane which is known to us, He intersects vertically, from above. … As the Christ, he brings the world of the Father. But we who stand in this concrete world know nothing, and are incapable of knowing anything, of that other world. The Resurrection from the dead is, however, the transformation: the establishing and declaration of that point from above, and the corresponding discerning of it from below. The Resurrection is the revelation: the disclosing of Jesus as the Christ, the appearing of God, and the apprehending of God in Jesus. …

Wow. There’s a lot in there! Barth seems to be saying that while the historical Jesus of Nazareth acts as the single visible point along the line of intersection of the planes of the fallen creation and the Kingdom of God, Jesus, as the Christ, is that second unknown plane. The Son, the second person of the Trinity, the Word of God, is spoken by the Father “from above” to intersect fallen creation vertically.

Carl Sagan gives a visual demonstration of how 3D beings might look down on 2D Flatlanders and intersect them from above or below.

When we proclaim the Resurrection, we proclaim our discerning of the single visible point of Jesus, and our acknowledgement by faith that He is the whole unknown plane that we cannot perceive. The Resurrection is, in this way, the identification of the point of Jesus with the whole plane that Barth previously described as “the world of the Father”. (To me, this sounds more like a description of the Incarnation than the Resurrection, but to Barth, these may be bundled together – they are often rolled into one “Christ event” by which God reveals Himself and His redeeming plans to man.)

Barth had also previously called this unknown plane “the final Redemption”. This squares a bit more easily with traditional articulations of the consequences of Jesus’ Resurrection from the dead: it is the first such raising and restoration of all the raising and restoration that God will effect on all creation, redeeming it from its fallen state. Identifying the point of Jesus as the visible part of the invisible plane of Christ can also amount to identifying his past Resurrection with the eventual Redemption of all things.

Already, not yet

But recall that Barth has affirmed that an infinitesimally small point – one point where the infinite God touches the finite creation, and where the redeemed Kingdom of God is inaugurated – paradoxically cannot touch anything. Barth uses one more geometrical image to make this point:

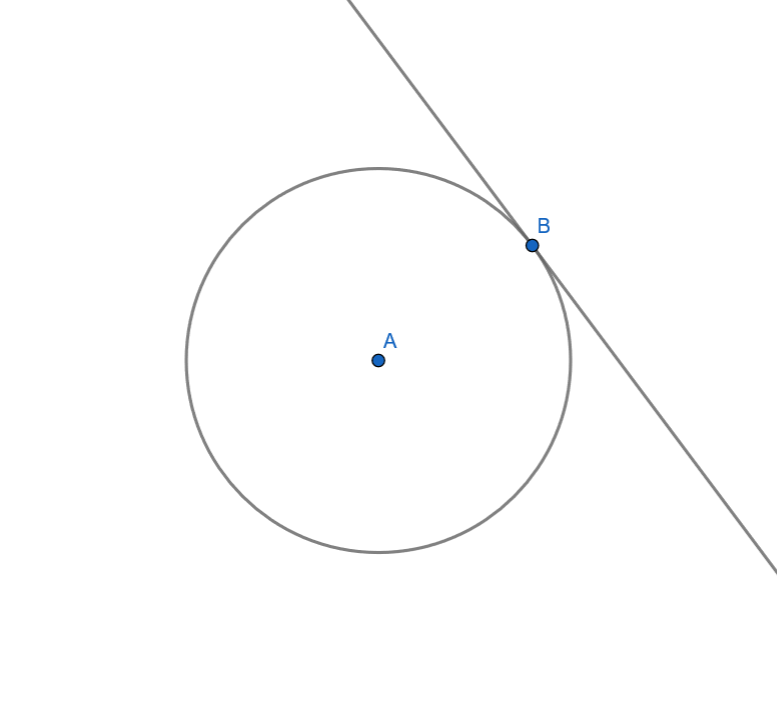

In the Resurrection the new world of the Holy Spirit touches the old world of the flesh, but touches it as a tangent touches a circle, that is, without touching it. And precisely because it does not touch it, it touches it as its frontier – as the new world.

The line lies tangent to the circle at point B, and does not ever touch it, but gets infinitesimally close.

A common phrase in Christian circles describes this phenomenon about the Kingdom of God first being established in the arrival of the King, Jesus Christ, but only being finally realized in the final Redemption – the Kingdom is both “already” and “not yet”. It is “already” at Barth’s visible point, but paradoxically this point does “not yet” touch.

Some ideas here are big and hard to think about, and need working out. But Barth packs a surprisingly math-heavy punch in a very short space! Barth fans should comment or set me straight on Twitter!

-

Barth, K. (1933). The epistle to the Romans (Vol. 261). Oxford University Press. ↩

-

John 1:1-3; 14, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. … The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.” ↩

-

Romans 1:4 and who through the Spirit of holiness was appointed the Son of God in power by his resurrection from the dead: Jesus Christ our Lord. ↩